Go-Far 2018: Eye on Estonia

Photo by: Alvin Ho

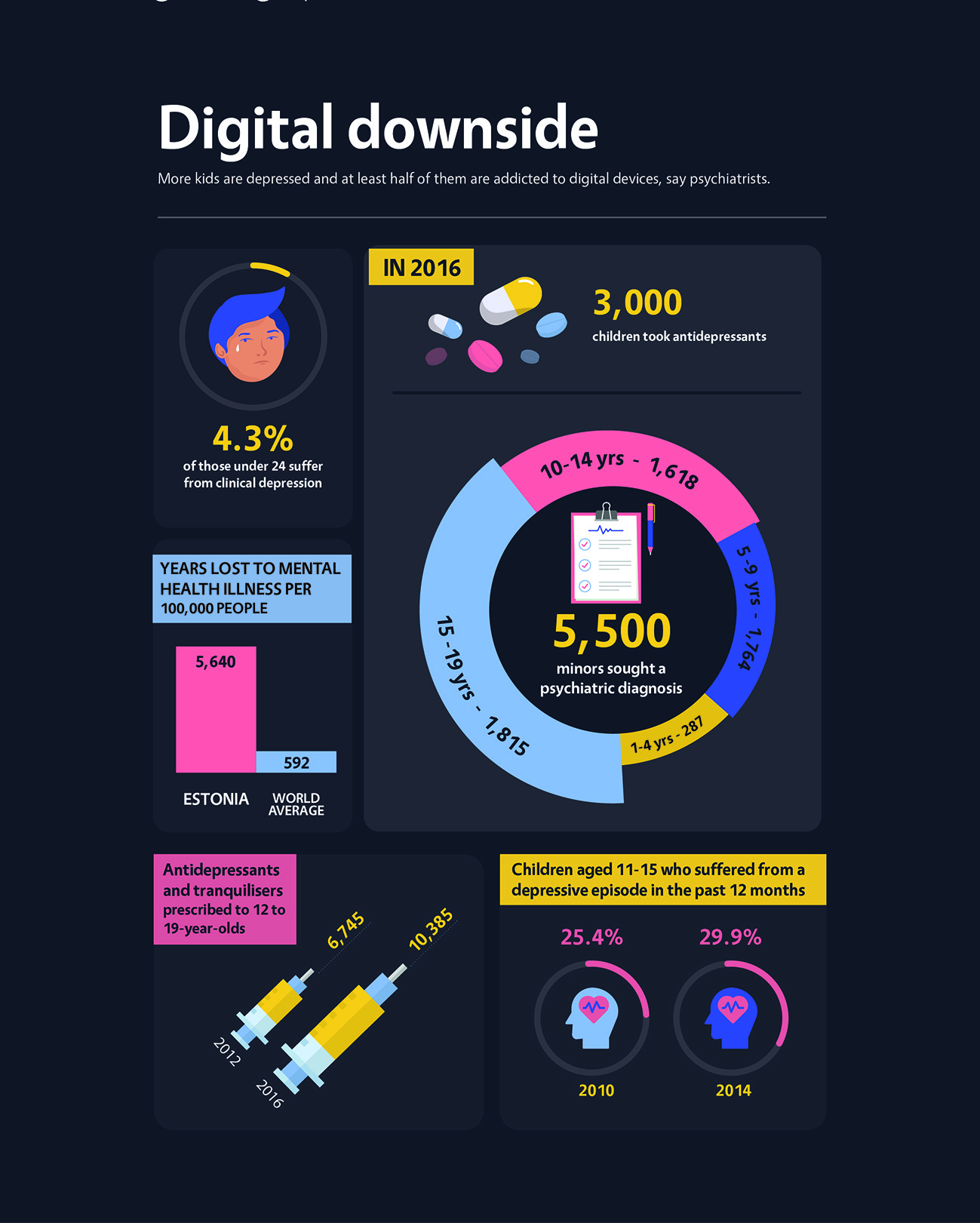

More Kids Hooked on Devices

Depression is on the rise because of an addiction to digital devices

By Khairul Anwar

The dark side of having gone digital is emerging in Estonia, with teenagers and even children as young as five reportedly spending some 15 hours a day using their digital devices.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), an estimated one in five of the Baltic state’s teenagers, or up to 40,000 youth, suffer from depression.

And while the rates of depression in youth are increasing worldwide, they are rising faster in Estonia, according to child and adolescent psychiatrist Dr Pavel Toropov of the North-Estonian Regional Hospital.

Downside of a digital society

Graphics by: Vanessa Goh

Half of Dr Toropov’s youth patients suffer from depression that is caused by addiction to digital devices, he said.

This is becoming a problem, especially in a tech-savvy country like Estonia, he added.

“Some children or adolescents sit in front of their computers for up to 20 hours a day, so that means their social skills worsen every day,” said Dr Toropov, 37.

Dr Toropov, who has 12 years of experience in child and adolescent psychiatry, drew an example from one of his previous cases. The child’s real name cannot be revealed due to privacy issues.

Oskar, 11, was constantly using his computer, and all his friends were online. He hardly interacted with his peers and others in the non-virtual world, as he did not have the ability to.

Like Oskar, many children and youth realise that they are unable to interact well with others. As a result, they continue to stay at home with their digital devices, and this creates a vicious cycle that is hard to break out of, said Dr Toropov.

Diagnosing depression caused by device addiction

For Dr Toropov and other psychiatrists, there is no concrete way to diagnose depression that is caused by the addiction to digital devices.

They use a checklist similar to the United States’ Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the standard criteria for the classification of mental disorders that is used by many medical practitioners worldwide.

The DSM, however, is not yet updated to include guidelines for the diagnosis of depression due to addiction to digital devices. Its latest edition was published in 2013.

To diagnose his patients, Dr Toropov arranges regular appointments with them his to understand their situation, before concluding with the diagnosis.

This process can take a few weeks, or as long as two to three years, depending on the child’s condition and progress.

“For now, it’s very subjective. I often sit with parents and their child, and the child isn’t talking to me. He is just watching something on his smartphone. That means he has a problem,” he said.

The WHO believes that the problem is serious enough to warrant a new framework to be drawn up, as it will helping doctors in Estonia and elsewhere with their diagnosis.

But this framework has received some criticism from many doctors worldwide as they felt that more research is still needed before the criteria is finalised.

Starting young

Anna (not her real name), 30, a single mother of a 10-year-old boy, believes that her son is not currently addicted to his device, but could well be on his way to addiction.

“When he is at home and the computer is easy to reach, it is very hard to get him away from it,” said the project coordinator, who has been raising her son single-handedly since he was about two years old, after her ex-husband left her.

Anna said that her son plays computer games for up to eight hours a day, and sometimes even longer, when she is on work trips overseas.

“He has forgotten himself there (in the virtual world). If I don't tell him to switch it off, he will not,” she said.

Even very young children appear to be victims of addiction to digital devices.

Primary school teacher Marii Juht, 31, said: ““I know a seven-year-old boy who prefers to stay inside all day and has no motivation to do anything because he prefers to play video games. He gets nervous and anxious being around people.”

When asked if her students might be too young to feel the effects of depression, Ms Juht said: “It is affecting them more than we think. I have seen four and five-year-old children who got very bad anxiety after (their) moms and dads asked them to put their smart devices away.”

“A kid got so upset when (her) mom took her screen away that she started screaming and hitting the wall. It took half a day to calm her down,” she added.

Familial issues

Parents can help to alleviate this problem by being stricter at home and limiting their children’s usage of digital devices, said Dr Toropov.

But some parents are also a part of the problem, according to Ms Käthlin Mikiver, 33, chief specialist at the Ministry of Social Affairs' Public Health Department.

She said that students from a strained family background are thrice as likely to experience depression as compared to those from a stable family.

A lack of parental guidance, as well as unhealthy family relationships, causes many youth to turn to devices as a coping mechanism, said secondary school teacher Matthijs Quaijtaal, 30.

Mr Quaijtaal said: “They are usually not equipped to deal with the problems, so they hide online or in games.”

Children are also spending more time on digital devices due to parents’ busy schedules, said Jack (not his real name), who is the manager of a computer café in downtown Tallinn.

“It’s very common for parents to leave their child here in the day to play games. A lot of them say they have to go to work, or they go shopping, and leave their child here for hours,” said the 21-year-old.

The café’s rates are cheaper than hiring a babysitter — it costs an average of seven euros an hour to hire one — which is a motivating factor for many parents to leave their children in Jack’s hands.

A three-hour-long morning gaming session costs only three euros at the café, which also offers discounted prices for members.

There is no official age limit at the café, Jack said, but employees exercise discretion, and turn children away if they “look too young.”

“If he looks five but he is here with his older brother, then it’s okay,” said Jack, as he waved goodbye to a 10-year-old boy and his younger brother.

They are regulars and Jack sees them almost every day.

“Homme näeme,” said the older boy, Estonian for “see you tomorrow.”